The conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has entered a new and more destabilising stage. A call for a pause in the fighting by leaders from the 8 member states of the East African Community (EAC) and 16 member states of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) was dismissed by Rwandan-backed M23 rebel forces, who have continued their offensive to seize more territory in the eastern DRC.

Following their taking of Goma (population of 2 million) and Bukavu (population 1.3 million), the respective capitals of North and South Kivu Provinces, the M23 has pressed farther south, capturing Kamanyola on its way to Uvira (population of 650,000), the third largest city in the Kivus. Another prong moved north of Goma toward Butembo (population of 280,000).

With the prospect of the M23 controlling the entirety of the 124,000 km2 of the mineral-rich Kivus, Rwanda would effectively be gaining a territory nearly five times its size.

Nor would this necessarily be the culmination of Rwanda’s territorial ambitions. Tensions have already started surfacing in Kisangani (in north central DRC) and Lubumbashi (in the south of the country) following the M23’s threats to push all the way to Kinshasa.

Les forces armées de la République démocratique du Congo (FARDC) are not providing much resistance to M23 advances. Burundian forces, numbering around 10,000 in South Kivu, have reportedly started withdrawing after M23 rebels overran Kavumu Airport and the adjacent air force base on their way to Bukavu. The proximity of the fighting to Bujumbura, just across the DRC border, risks leading to a direct confrontation between Burundian and Rwandan troops.

Ugandan forces, meanwhile, have also entered the DRC and seized Bunia (population of 900,000), the capital of Ituri Province. The aim of the Ugandan deployment is ostensibly to counter the wantonly violent criminal group, the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), which has been menacing communities on both sides of the Ugandan-DRC border for years. However, the M23’s simultaneous drive towards Butembo enroute to Bunia has raised suspicions of potential coordination between the M23, Rwanda, and Uganda. Top Ugandan generals and senior government advisors have commented favourably on the M23’s cause and narrative, a markedly different tone than when the M23 seized Goma back in 2012.

During the battle for Goma in January 2025, a firefight between the M23 and SADC Mission in the DRC (SAMIDRC) forces, who were in the DRC to help contain the M23 threat, led to the deaths of 20 soldiers from South Africa, Malawi, and Tanzania. About 1,300 SAMIDRC troops remain confined to their bases in Goma and Sake under the watch of M23 fighters after negotiating a ceasefire. The deaths and the potential of Rwanda gaining leverage over its giant neighbour have further accentuated the regional tensions underlying this conflict.

The DRC’s already dire humanitarian situation has been worsened with the population displacements caused by M23 advances. More than 500,000 people in the Kivus were displaced as a result of the M23’s latest push. There are now an estimated 7 million Congolese displaced within the country, the majority in the eastern provinces.

The United Nations (UN) estimates that 3,000 people, mostly civilians, were killed during the M23’s attack on Goma, underlying the degree of violence employed. Many say the death toll is much higher. The risk of mass atrocities is also high in a region where predation by rebels, militias, and government forces is common. The UN has warned of surging child recruitment, abductions, killings, and sexual violence.

As the fighting expands, these human costs as well as wider instability for the entire region are likely to escalate. The First and Second Congo Wars are estimated to have resulted in the deaths of 5.4 million people and economic costs in the DRC alone of more than $11 billion (or 29 percent of its GDP at the time).

A Regionalised Crisis

The M23 is advancing faster than previous insurgencies from the east during the First (1996–1997) and Second Congo Wars (1998–2003), with the possibility that they could attempt to march on Kinshasa.

Aside from the DRC and Rwanda, Burundi is the country closest to the vortex of this regionalised crisis. The Burundi National Defence Force (BNDF) has battled the M23 alongside the Congolese military, a government militia called Wazalendo, and Romanian mercenaries, who departed after Goma fell. Rwanda-Burundi relations have been frosty since 2015 with each country blaming the other for supporting rebels seeking its overthrow.

Rwanda also accuses Burundi of being part of a collection of forces fighting alongside the DRC that includes the Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda (FDLR), remnants of forces implicated in the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. South Kivu has witnessed heavy fighting between M23 and Burundian forces, who evidently started retreating to prevent encirclement as the rebels split up into three prongs, including one through Uvira, which faces Bujumbura across Lake Tanganyika—a 25-minute drive. Burundi says it has not retreated, but its forces reportedly crossed back into Bujumbura to reorganise. South Kivu also hosts Burundian rebels who have engaged in pitched battles with Burundian forces since 2021.

Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi has also relied on SADC forces to fight the M23. This led to the May 2023 authorisation of the 1,300 SAMIDRC forces in the DRC (out of a maximum commitment of 5,000 troops). South Africa holds Rwanda ultimately responsible for SADC’s troops losses and has warned that further attacks would be treated as an “declaration of war.” Rwandan President Paul Kagame’s rejoinder was just as terse: “If South Africa prefers confrontation, Rwanda will deal with the matter in that context any day.”

Malawi withdrew its troops in the face of the M23’s ongoing advance while Tanzania is playing the role of bridge-builder within the EAC. South Africa has deployed additional troops and equipment to the DRC.

SAMIDRC was deployed under a SADC collective security treaty that compels immediate collective action if a member state is attacked or facing a complex internal national security threat. Should SAMIDRC become an all-out warfighting mission, it would be reminiscent of the Second Congo War when SADC troops came to the aid of then DRC President Laurent Kabila against the Rwandan and Ugandan assault.

Tshisekedi has meanwhile requested Chadian military support to combat the M23. The regional crisis is therefore metastasising into a pattern that harkens back to the First and Second Congo Wars that drew in nine African countries, the largest African multinational war ever witnessed.

The M23’s Shifting Calculus and Methods

The M23 has imposed political and administrative governance structures in the areas it controls—a practice it did not employ in its campaigns a decade ago. It is also absorbing defeated Congolese government forces, after retraining and political education, another new modus operandi. The M23 now also operates as the armed wing of the Alliance Fleuve Congo (AFC), bringing together anti-government groups, armed movements, and political actors in parts of the DRC outside the east. The alliance is led by Corneille Nangaa, who hails from the west and was twice President of the Independent National Electoral Commission. Nangaa is calling for the overthrow of the government in Kinshasa.

The M23 has also expanded its control of lucrative mining sites, including Rubaya (Congo’s largest coltan producer), which it seized in May 2024. “They [the M23] are targeting minerals in addition to government posts, the army, police, and state enterprises,” says Amadee Fikirini, Life Peace’s Country Director for Congo based in Bukavu. Rubaya produces 1,000 tons of coltan annually—half the DRC’s output. Other areas of M23 control are rich in cobalt and lithium, which are critical to electric vehicle batteries. The region is also rich in gold, which is reportedly the key source of revenue for the M23.

A UN investigation found that the M23 earns $800,000 monthly from the taxes it imposes on miners and traders of coltan alone, partly explaining its military expansion in recent years. Calls are growing for the European Union (EU) to suspend a memorandum of understanding (MOU) it negotiated with Rwanda in 2024 to “boost the flow of critical raw materials for Europe’s microchips and electric car batteries.” Part of the MOU entails developing infrastructure in Rwanda for raw materials extraction, as well as health and climate resilience, for which the EU committed $941 million to Rwanda.

Diplomatic Endeavours

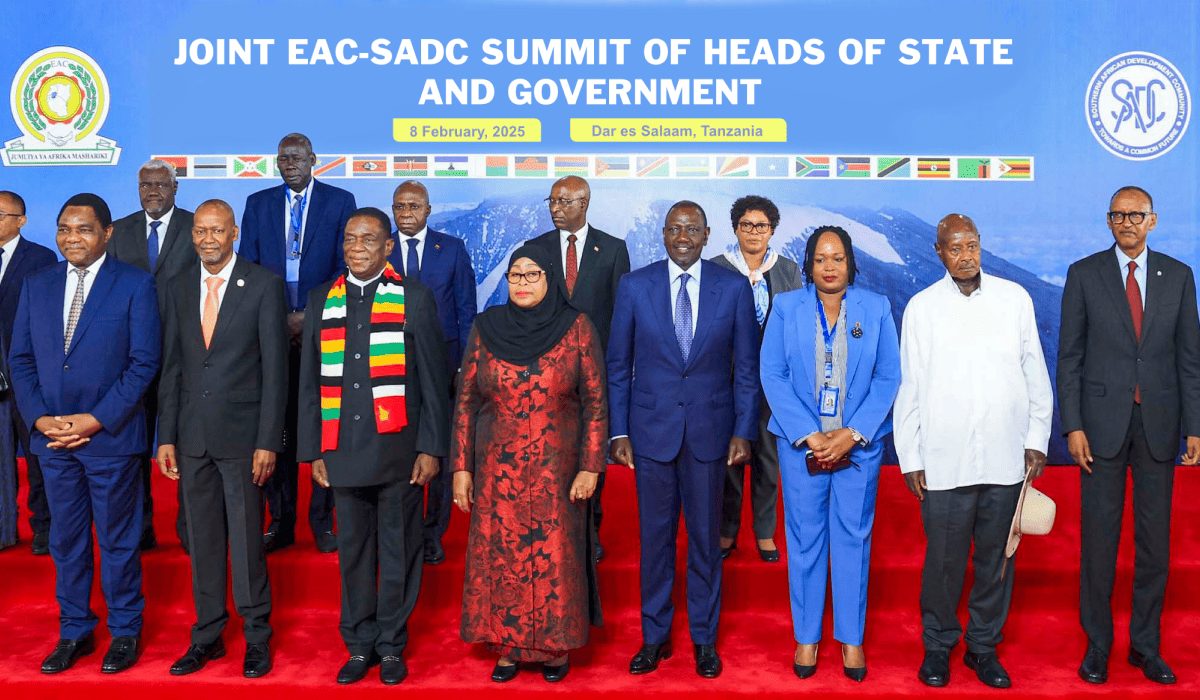

Two summits of the EAC, one in Nairobi and a joint EAC/SADC meeting in Dar es Salaam in January 2025, ended without clear agreement. Tshisekedi skipped the Nairobi summit while Burundi’s President Évariste Ndayishimiye skipped the one in Dar es Salaam. There is tension between the Congolese government and the EAC over Tshisekedi’s expulsion of the EAC Regional Force (EACRF) from the DRC in 2023, a year after it deployed. He accused it of being ineffective and unwilling to fight the M23. The EAC pushed back, noting that it reached a ceasefire with 53 of the nearly 120 armed groups in eastern DRC and that the M23 did not launch attacks for 8 months during its deployment thanks to diplomatic efforts.

The EAC also balked at the Congolese government’s use of militias and foreign mercenaries, which would have put EACRF troops on the same side as these non-statutory forces in the battle against armed groups. It also insisted on finding a comprehensive solution to the question of citizenship for Congolese of Rwandan descent, to include the Banyamasisi, Banyamulenge, and others. This issue has long been manipulated by national authorities for political purposes, leaving these communities stateless at times and pushing them into rebellions, which have always started in the east—five cities in particular: Bukavu, Bunia, Goma, Kisangani, and Uvira.

The Dar es Salaam summit sought to bridge regional differences by bringing the two blocs together. It called for an immediate ceasefire, direct talks with the M23 and other nonstate actors, and a plan to disengage Rwandan forces by harmonising efforts to neutralise the FDLR. Leaders from both blocs gave themselves 30 days to reassemble and hear back from EAC and SADC chiefs of defence on a ceasefire.

The Congolese Catholic Bishops Conference (CENCO) also launched a diplomatic initiative, holding high-level meetings in the DRC and the region. These efforts led to a brief pause and pullback of M-23 troops from Bukavu, before they moved in again and seized the city.

Possible Scenarios Moving Forward

The interests driving the M23 and its backers are varied and unclear. Plausible scenarios or combinations thereof, can be sketched from the debates by Congolese professionals and activists on the ground in Goma, Bunia, Bukavu, Uvira, Kisangani, Katanga, and Kinshasa, as well as among the Congolese diaspora.

Scenario 1: De Facto Military and Administrative Control of the Kivus

Many Congolese refer to this scenario as “annexation by Rwanda.” It could plausibly strengthen the M23’s hand at the negotiating table and/or create the conditions for a permanent or semi-permanent sphere of Rwandan control.

Scenario 2: National Rebellion

This would be a repeat of previous wars in the DRC, which crystallised in the east and spread to the west and ultimately Kinshasa. The AFC-M23 alliance has taken on a national narrative and called for the overthrow of Kinshasa. Some analysts believe that capturing political power is the ultimate objective of the offensive. The aim would be a regime dominated by the AFC or components sympathetic to it.

Scenario 3: Protracted Regional War

If diplomacy fails, the armed protagonists may decide to pursue military solutions, a scenario that would be a repeat of the Second Congo War, which pitted the DRC government and its SADC allies on one side and Uganda and Rwanda on the other.

Diplomatic Initiatives

Each of these scenarios entails huge and likely long-lasting human, social, and financial costs for all parties. To avoid these outcomes, an alternative, diplomatic resolution is needed.

The DRC faces both a domestic and externally driven crisis. To de-escalate and walk back this conflict, both dimensions must be addressed.

Domestically, observers have long argued that since independence, the DRC has been hamstrung by governance structures that lack legitimacy and accountability. Its leaders have tended to treat the country as private property in much the same way as King Leopold II of Belgium. This is demonstrated by the perpetual inability of the FARDC to protect Congolese citizens—and the need to rely on external partners for the DRC’s security.

To remedy this requires strengthening and upholding democratic checks and balances that genuinely represent citizen interests and promote transparency. This includes an independent judiciary and elections commission to register the will of the people and ensure an executive respects the rule of law. It will also require a more independent parliamentary process that provides oversight of government expenditures, including transparent regulation of the mining sector. A more robust oversight of the security sector is also required to ensure that allocated resources are used to maintain professional, disciplined, and well-trained and equipped armed forces to defend the country’s nine international borders.

Reforms will also require addressing the issues of citizenship among the Congolese of Rwandan descent in the east of the country and upholding previous commitments to fully integrate them into Congolese society.

Georges Nzongola-Ntajala, a veteran Congolese intellectual and retired diplomat argues that the Sovereign National Conference (1991-1992), where he advised the late Étienne Tshisekedi, was the first serious attempt to address these problems. The DRC may need a second, inclusive national conference, assembling all political and social forces under the stewardship of the country’s highly respected religious leaders like in 1991-1992 to address the current crisis. Such a national conference could draw lessons from other conflict resolution efforts in the DRC, including the Inter-Congolese Dialogue.

The external dimensions of the DRC’s crisis will require a pullback by the M23 and its backers as called for by the EAC and SADC leaders. The unanimously adopted UN Security Council Resolution of February 21, 2025, condemning the M23 offensive and calling on Rwanda to cease its support for the M23 and immediately withdraw from the DRC builds on an earlier African Union resolution condemning the M23 attacks. The EU’s subsequent suspension of security assistance to Rwanda is in line with these resolutions.

A ceasefire may require the deployment of a multinational AU observer force comprised of countries acceptable to all belligerents. A ceasefire would need to be supported by the resumption and merging of the Luanda and Nairobi negotiating processes to realise a longer term resolution. This would entail a verifiable agreement between the DRC and Rwanda, backed by a joint commission to monitor commitments. This could be modelled after the South African-mediated Pretoria Agreement in 2002 that paved the way for Rwanda’s exit from the DRC and a mechanism for joint operations with the Congolese government to address the FDLR.

Lessons, too, can be drawn from the 1999 Lusaka Agreement, which orchestrated the cessation of hostilities from the First Congo War, including a process for the orderly withdrawal of external actors and a mechanism to pursue disarmament and reintegration of former combatants into the Congolese military.

A multinational African guarantor mechanism with international backing would likely be a critical element of such an agreement to provide assurances to all sides that commitments are being upheld.

The solutions to the DRC’s complex problems are to be found within the Congolese experience but must be backed up by African support and engagement to be realised—and to avert the enormous costs to the continent generated by previous conflicts in the DRC.

This article was first published by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies and can be accessed here.

Paul Nantulya is a Research Associate with the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.